The age of a “flat,” hyper-globalised world is giving way to something bumpier. As Financial Times columnist Rana Foroohar argues in her book Homecoming: The Path to Prosperity in a Post-Global World, “the reign of globalisation as we’ve known it is over,” and a new era of local and regional enterprise is dawning. Global crises, from pandemic shortages of PPE to the disruptions of the Ukraine war, have exposed the fragility of far-flung supply chains. Foroohar notes that half a century of prioritising efficiency over resilience (what she calls a neoliberal fixation on cheap capital, energy, and labour) has led to inequality and insecurity.

Now, “the pendulum of history” is swinging back: technological advances and shifting policies make it possible to keep “operations, investment, and wealth closer to home.” Economists and business leaders increasingly frame localisation, regionalisation, and decentralisation as the defining features of the next phase of the world economy.

The end of the flat world

In the late 1990s and 2000s, globalisation promised cheap goods and rapid growth. Thomas Friedman’s famous dictum “The World Is Flat” captured the mood of an era when companies built factories and sourcing networks anywhere on the planet. But Foroohar and others now contend that the model has run its course. “The world isn’t flat – in fact, it’s quite bumpy,” she writes, highlighting how Covid lockdowns and geopolitical conflict exposed the vulnerabilities of global trade.

Globalisation was built on three pillars – ultra-cheap capital, energy, and labour – and all three are changing. Companies now face rising costs “everywhere” and must “reconfigure how they think about their operations.”

This shift does not mean a turn to isolationist protectionism. Foroohar distinguishes that as dangerous nationalism, favouring instead a regionalism and “friend-shoring” that aligns trade with shared values and resilience. She argues that questions like “What are our values as a nation? Who else shares our values, and how can we do business with them?” can guide the restructuring of supply networks.

Food systems and local resilience

The food industry provides a stark illustration of the global-vs-local debate. The Covid-19 shock and subsequent spikes in grain and fertiliser prices prompted urgent questions: are locally based food systems more robust than global value chains? Evidence suggests a mix. The most resilient food supply systems are those with strong operational, relational, and structural capacities at every stage of a shock. Yet many countries failed to convert short-term fixes into lasting resilience, leaving them exposed to the next disruption.

Local supply chains, once sidelined, became critical during the pandemic. “Local supply chains were necessitated as an emergency response,” researchers note, demonstrating transformational resilience. Post-Covid, resilience remains a strategic priority, with continued investment in local operations so these networks “thrive with embedded resilience.”

Still, localism has limits. Regions with scarce resources, like the wheat-importing countries in Africa or the Middle East, still depend on trade. The emerging consensus is a balanced model of regionalised, not self-reliant, supply chains.

Tech and industry reconfigured

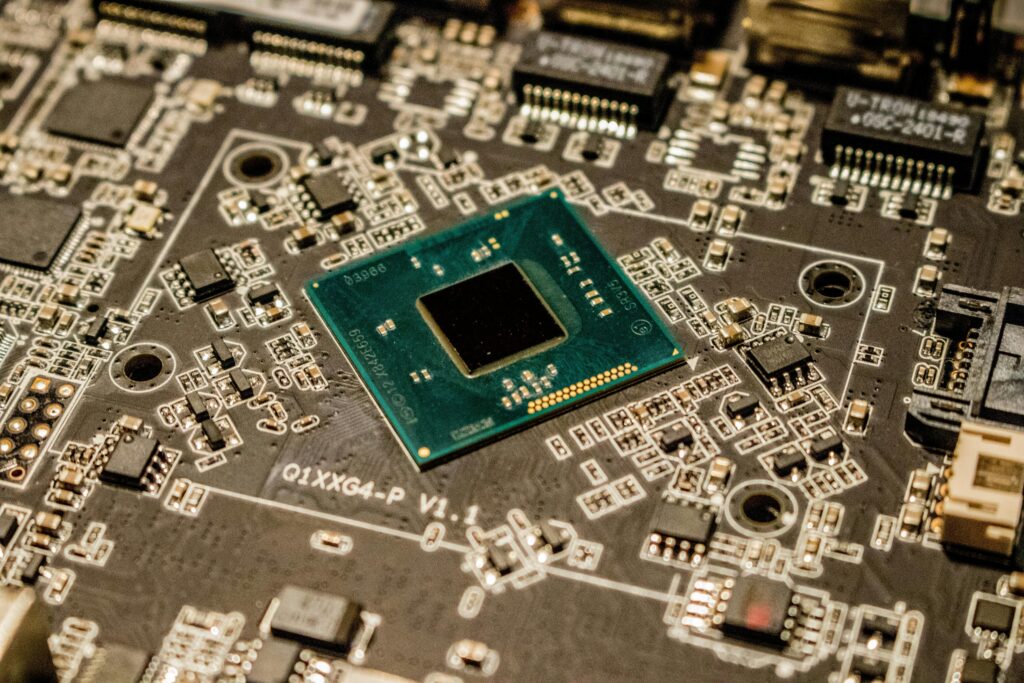

Technology and manufacturing are undergoing a similar re-evaluation. The semiconductor shortage exposed the dangers of concentrated production, prompting governments and corporations to examine vulnerabilities in chip supply. The response has been reshoring and targeted subsidies. Semiconductor, electric vehicle, and rare-earth mineral sectors are now “strategic,” requiring choices about where and how operations occur.

Healthcare is another case. The Covid-19 vaccine scramble highlighted the risks of distant production. Many regions are investing in local vaccine manufacturing to prevent future shortages. Building new biotech plants while pairing them with global know-how exemplifies how resilience can coexist with global integration.

Advanced economies are also seeing a revival in broader manufacturing. Foroohar emphasises the industrial strength hidden in family-owned factories, which proved adaptable during the pandemic. Textile mills in North and South Carolina, for instance, responded to mask shortages by retooling overnight, drastically reducing unit costs. This demonstrates the practical adaptability of local clusters of suppliers.

Similar shifts are emerging in other sectors. Auto manufacturers and energy firms are forging regional networks for batteries and components. State governments and the EU are investing billions in localised renewable energy and battery manufacturing, knitting together factories, miners, and research institutions in closer proximity. Even corporate behemoths are now evaluating partners not just for cost but for national interest, echoing the more patriotic capitalism Foroohar explores.

Regionalism, values, and the road ahead

Across industries, regional and local resilience is becoming as valued as global scale. This rebalancing is as much political as economic. Foroohar cautions that this is not about embracing extreme nationalism but recognising that trade alliances carry value judgments. “End of pure economic globalisation,” she warns – countries now ask if trading partners share core political and social values. This sentiment underpins the growing practice of “friend-shoring”: preferring supply chain links with democracies or allies. By focusing on regionalisation and regional hubs, businesses can align trade with trust and strategic alignment.

Policy reflects this shift. The US and EU have linked subsidies to domestic investments in sectors deemed strategically important. Japan has instituted export controls on rare materials to encourage internal sourcing, and India has revived incentives for chip factories and vaccine plants. Foroohar sees these measures as evidence that national security and global business cannot drift apart. She calls for a “re-mooring of national interest and the global economy,” ensuring supply chains serve citizens as well as shareholders.

No one expects a return to Cold War-style autarkies. Many see a middle path where countries maintain open trade in bulk commodities yet localise manufacturing and essential services. Food and tech examples illustrate this hybrid model: global networks distribute grains or semiconductors, while local nodes and regional partnerships handle just-in-case inventory and critical components. Foroohar argues this could yield broader prosperity. By blending efficiency with resilience, economies can avoid a race-to-the-bottom in wages and carbon emissions while supporting local jobs.

Ultimately, Foroohar’s thesis is that the world can rediscover growth “from the middle out” rather than trickle-down. Localisation does not mean isolation; it means balanced globalisation that prizes sustainable communities and supply security alongside open markets. Advances like 3D printing and renewable energy make it possible to rebuild industries closer to consumers, fostering “place-based economics” where wealth circulates locally.

The stark lesson of recent years is that long supply lines and political friction often go hand in hand. As Foroohar and other researchers note, repeatedly exposed global chains tend to break when the next shock comes. Moving forward, more countries and companies are betting that local is the new global: that shorter, trusted connections – in food, chips, or medicines – can make economies more adaptable. In Rana Foroohar’s words, we may be witnessing a historic “homecoming” of industry and capital to places that were left behind by the old model, re-shaping strategy from Silicon Valley to small businesses worldwide.