With automation and ‘AI agents’ as the current buzzwords of the modern workplace, the fear that human-operated jobs will soon be replaced has never been higher. In a not-too-distant world where almost every work task can be performed better by robots, where does that leave us as humans (in Western industrialised economies), and our current lifestyle, spending roughly 90,000 hours of our lives at work?

In 2016, Elon Musk told CNBC “there’s a pretty good chance we end up with a universal basic income, or something like that, due to automation. I’m not sure what else one would do”. He added, “The much harder challenge is, how are people going to have meaning? A lot of people derive their meaning from their employment. So if there’s no need for your labour, what’s your meaning? Do you feel useless?”.

Critics argue UBI will lead to a bloated and unsustainable welfare state, dismissing it as an unrealistic utopian vision. As the UK deals with growing inequality, a cost-of-living crisis, insecure work and a crippled welfare system, how feasible is UBI, and is it something we can expect in the future?

What is UBI?

Universal Basic Income is often defined as an unconditional cash grant paid by the state to every individual, without means-testing or work requirements – citizens have the right to a regular payment. However, the level of compensation is the central debate. An oft-repeated phrase is that “affordable UBI is inadequate, and adequate UBI is unaffordable”. Payouts of £8,000 a year are touted as a minimum viable offering, stated to reduce poverty rates in the UK from 18% to 5%. Other variations of UBI from the 2020 Scottish Feasibility study include a full income to cover all living costs, or a ‘basic’ scheme of £3,800 per year, acting more as a ‘symbolic’ UBI.

Benefits of UBI

Advocates claim that UBI could dramatically improve economic security, reduce administrative burden, and help people focus on more ‘meaningful’ pursuits with basic survival needs being covered.

Poverty reduction

By design, UBI prevents people from falling below subsistence levels. Models have shown that UBI around the current rates of benefits would lift a significant share of poor people in the UK out of poverty, from around 18% to 5% poverty rates. Even a more moderate level of compensation would still help thousands of households.

Reduced administrative burden and welfare stigma

The automatic, untested nature of UBI payments would have a number of positive effects. The House of Commons research briefing noted that under UBI, “the intrusiveness, administrative burden and human costs of benefits (sanctions, low take-up, anxiety etc.) virtually disappear. The social stigma around benefits, that of being labelled a “skiver” will no longer exist.

Higher life satisfaction

With a greater ability to choose how time is spent, individuals can pursue more ‘meaningful’ projects rather than purely working for survival needs. In evaluations of unconditional payments, recipients have reported significantly higher life satisfaction. For example, the basic-income trial in Finland saw participants reporting far higher wellbeing scores and lower rates of depression.

Education and crime rates

Historical income-guarantee experiments have shown positive side effects. For example, the 1960s US Negative Income Tax pilot showed that children in beneficiary families attended school more regularly, and crime rates fell, as economic stress on families eased. While the UK hasn’t run an experiment like this yet, it is reasonable to expect similar outcomes.

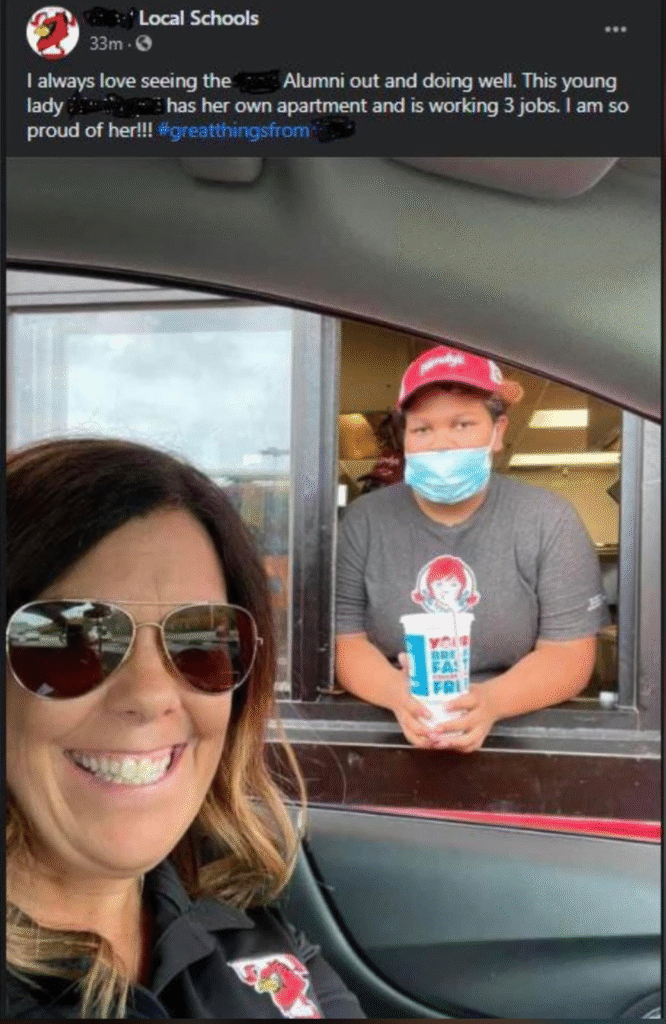

Avoidance of ‘exploitative work’

With a guaranteed safety net, people have the ability to refuse exploitative jobs, and instead follow more ‘meaningful’ pursuits, in whatever form that might take. Whether it be enrolling in further education, caring, or launching a purpose-driven business, the limiting factor of needing to pay bills is removed. Each adult in a household would have economic independence, through each partner in a couple getting paid rather than only one household payment. Freeing people from the notion of ‘working to survive’, UBI could in theory improve job matching and overall satisfaction. As Bregman argues, UBI would allow everyone “the chance to do work that is meaningful”.

Criticisms and trade-offs with UBI

The main objections to UBI relate to the cost, incentive and fairness of the scheme. In order to implement a generous UBI, steep tax increases would be required, while a small UBI would barely improve the standard of living. Some analyses have shown that high-level UBI schemes would require marginal tax rates as high as 70-85% on top incomes.

Huge cost

While all estimates vary, the common theme is that a full UBI would be very expensive. A generous UBI scheme, like £1,000 per month for every adult would have a gross cost of £650bn per year. After replacing benefits and accounting for tax changes in the UK welfare system, the net additional cost could be between £200-£300bn per year. However, as current social spending in the UK stands at about £379bn per year, a more modest UBI could be possible with fund reallocation. However, even at its lowest plausible net cost, UBI would require raising additional revenue or shifting current spending priorities.

Ultimately, it all depends on the agreed generosity of the UBI payment itself.

Higher taxes or cuts

Most models assume large tax hikes, like raising income-tax rates by 8-20+ points, removing tax-free allowances or adding new levies. A flat UBI gives the same cash to everyone, which means wealthier people actually win back less or lose out. Middle earners would face higher tax rates to finance it. A significant tax increase is a hard sell, even if it improves welfare for poorer families.

Work disincentives

One common concern is that unconditional pay would reduce people’s drive to work. Unlike benefits, UBI puts no obligations on recipients. Critics fear that it would effectively pay people to stay unemployed or out of education. There is some evidence for this fear too – US ‘negative income tax’ experiments in the 1960s-70s saw small but statistically significant drops in labour supply (roughly 7% for men and 17% for women).

One-size-fits-all issues

A blanket approach to UBI wouldn’t accommodate personal circumstances – every adult receives the same amount regardless of housing cost, disability, or family size. To combat this, extra means testing would be required in areas of higher rent, or for disabled people, for example. Single-adult households would also become worse off.

Political challenges

Other than cost concerns, UBI brings up a number of political challenges. Public support for UBI in the UK is mixed. A 2024 YouGov poll found that 46% of Britons support introducing UBI in principle, versus 33% opposed. Support is higher among Labour voters (61%) and lowest among Conservatives (21%). Roughly half seem to agree with claims of quality of life improvements and cutting poverty, but only a quarter believe the government can afford it. The perception of huge cost, combined with worry about tax rises, makes UBI a difficult political sell.

Immigration concerns

With the UK recently experiencing an all-time high net migration of 906,000 in the year to June 2023, tensions over small boat crossings and asylum applications are high. Negative public opinion towards immigration tends to weaken support for universal welfare programs, fuelling resistance toward policies perceived as benefiting non-citizens equally.

Cultural shifts

In Western industrialised nations, identity and social worth are often tied to employment. How many times have you been asked “what do you do?” as a default icebreaker?

Cultures with strong Protestant work ethics often equate any work, regardless of its usefulness to society, as a duty. Thinkers such as David Graeber would argue that the real obstacle to UBI isn’t money, but a deeply ingrained belief that people need to ‘prove their worth’ by submitting to meaningless jobs. Along these lines, it implies that there’s a distinct lack of trust, in that humanity will stop creating, caring, dreaming, etc. if they aren’t forced to. By decoupling income from employment, society would have to shift from valuing hours worked to valuing meaningful contribution, in whatever form that takes.

Unfortunately, for most, the moral obligation to work is likely too strong for UBI to break, even in the face of complete madness.

Conclusion

UBI would mark a significant ideological shift amongst Western industrialised economies, sparking interest and debate worldwide. With the opportunity to guarantee a secure income for all, leading to reduced poverty and unlocking individual human potential, UBI supporters make a highly appealing case.

With trials and studies showing that these are not unfounded claims, wellbeing and poverty relief in low-to-middle income groups would greatly increase. However, making UBI feasible in the UK would demand some difficult trade-offs. A willingness to overhaul the tax-benefit system, as well as increasing revenue and redistributing income at unprecedented levels would be required.

UBI is an ambitious social contract change. While advocates see it as a way of creating more meaning and choice in people’s lives, freeing them from ‘pointless toil’, sceptics remind us that perhaps simpler reforms can be made at a lower cost. For now, small pilot programs and spirited debate continue to explore the potential of UBI, asking us whether the UK is ready for such a monumental change.